Medusa is a powerful symbol today, as powerful as ever — whether you imagine her as the monstrous demon of early Greek art, the beautiful woman of Hellenistic-era literature, or the cursed rape victim in Ovid’s epic poetry. More recently she has appeared as a stop-motion monster (Clash of the Titans, 1981); a woman embittered in old age (Percy Jackson, 2005); an adorable floating head (Hades, 2020).

And sometimes she has also become an afrocentrist symbol. You may have heard that Medusa was originally a Libyan goddess — or alternatively, that the Greek myth of Medusa was designed to demonise black women.

|

| Late antique mosaic of Medusa from Hadrumetum, Tunisia (Sousse Archaeological Museum) |

What’s the historical low-down? Well, in an important sense it doesn’t matter. Whether or not Medusa was African in the 7th century BCE, that doesn’t determine whether she’s African now. Myth evolves. Aeneas didn’t originate in Roman myth, but he’s still an important part of Roman myth. Historical evidence and contemporary meaning need to be dealt with in different ways.

Well, did Medusa start out as Greek, or not?

The short answer is yes, she was invented by Greeks. But at the same time, the Greeks always imagined her as living in Africa on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean. In the very earliest sources, she lived on an island in the Atlantic.

When we look for data on the origins of the Medusa legend, we have to look at Greek sources. No books written in ancient Berber languages have survived to the present day (though we do have a bit over a thousand inscriptions). Here’s the earliest source, composed around 700 BCE:

... and the Gorgons who dwell beyond glorious Ocean

at the edge towards the night, where the clear-voiced Hesperides are:

Sthenno and Euryale, and Medusa who suffered woes.

She was mortal, but the others are immortal and ageless,

the two of them: with her alone the dark-haired one [Poseidon] lay down

in a soft meadow among spring flowers.

When Perseus cut her head off from her neck,

great Chrysaor and the horse Pegasus sprang forth ...

Hesiodic Theogony 274–281 (tr. Most)

Most of our geographical information comes from ancient stories about Perseus. Perseus had foolishly promised that he would provide the Gorgon’s head as a gift, and Polydectes, king of Seriphos, held him to his word. Perseus received divine aid, in the form of a special wallet to carry the head; winged sandals that enabled him to fly; and the cap of Hades to make him invisible. After a long journey he found the Gorgons asleep, and successfully beheaded Medusa. A Roman-era mythographic text describes the Gorgons as follows:

The Gorgons’ heads had hair intertwined with dragons’ scales, and enormous tusks like boars, and bronze arms, and gold wings with which they could fly. And they turned anyone that saw them to stone.

pseudo-Apollodorus, Library 2.4.2

Perseus escaped from the other two Gorgons using the cap of Hades. On his way back to Greece he paused in the Maghreb and turned the Titan Atlas to stone. And that is why we have the Atlas Mountains in Morocco and Algeria.

|

| Medusa as portrayed in Clash of the Titans. Left: the 1981 film, with stop-motion animation by Ray Harryhausen. Right: the 2010 remake, with computer generated imagery. |

Other details appear in different sources: Medusa was originally a beautiful woman who was transformed; she remained beautiful (but deadly) after her transformation; she was a rape victim, and cursed by Athena; her head was set on the shield of Athena; and so on. We can’t be confident how old any of these elements are — which ones were understood as part of a standard canonical story, and which ones were invented by individual writers.

The names are the clearest indication that the story has Greek origins. Ancient Greek names are normally built out of meaningful Greek words. Medusa and her family are no exception.

- Medusa (Greek Médousa, Μέδουσα) is a feminine participle of the Greek verb μέδω: μέδουσα ‘guarding, governing’. The name has several parallels in Greek culture: two other mythological characters called Medusa (a daughter of Priam, ps.-Apollodorus 3.12.5, Pausanias 10.26.1; a daughter of Sthenelus, ps.-Apollodorus 2.4.5), and the masculine form Médōn, a character in Homer (Iliad 2.727, etc.).

- Sthenno and Euryale, her sisters (Sthennṓ Σθεννώ, Euruálē Εὐρυάλη). ‘Sthenno’ comes from Greek σθένος ‘strength’; note the masculine parallels Sthénnios, Sthénon. ‘Eury-ale’ comes from εὐρύς ‘wide’ plus ἁλ- ‘sea’: note the masculine form Eurúalos, another Homeric character (also Anchíalos ‘next to the sea’, Amphíalos ‘sea-surrounded’, etc.).

- Phorcys and Ceto, the sea divinities who are their parents (Phórkus Φόρκυς, Kētṓ Κητώ). ‘Phorcys’ comes from Greek φορκός ‘white, grey’ (Greek poetry regularly refers to sea foam as white). ‘Ceto’ comes from κῆτος ‘sea monster, whale’.

- Gorgo(n) (Gorgṓ Γοργώ or Górgōn Γόργων) comes from Greek gorgṓps γοργώψ ‘rapid faced, grim faced’, a word that Sophocles uses to describe the goddess Athena.

|

| ‘Dusa’ wielding a feather-duster: Hades (2020; art direction by Jen Zee) |

How did Medusa come to be Libyan, then?

‘Libya’ is a very misunderstood name. When ancient Greek writers say ‘Libya’, they don’t mean the modern country. Libúē (Λιβύη) was the ancient Greek name for the entirety of the Maghreb, that is, northern Africa all the way from the Strait of Gibraltar to what is now western Egypt. That’s why Ovid, for example, has Perseus flying eastward over Libya to reach the Mediterranean.

Ancient sources do indeed put Medusa in or near northern Africa. It’s just that if they’re thinking of a real place, it’s Morocco, not Libya.

Here’s a run-down of where ancient sources placed the Gorgons.

| Source | Date | Medusa’s location |

|---|---|---|

| Hesiodic Theogony 274–281 | ca. 700 BCE | ‘beyond the Ocean, at the edge of night’, in the same region as the Hesperides (‘nymphs of the west’) |

| Cypria fr. 30 ed. West | 600s/500s BCE | ‘Sarpedon’, an island in the Ocean |

| Pindar, Olympian ode 10.44–48 | 476 BCE | in or near Hyperborea |

| Pherecydes fr. 11 ed. Fowler (= FGrHist 3 F 11) | mid-400s BCE | Ocean |

| Herodotus, Histories 2.91 | 420s BCE | Africa (‘Libya’) |

| pseudo-Apollodorus, Library 2.4.2–3 | 1st cent. BCE? | Ocean |

| Ovid, Metamorphoses 4.612–620, 4.769–803 | 8 CE | three days’ flight (for Perseus) west of the Atlas Mountains |

| Lucan, Civil war 9.619–699 | 60s CE | border of Africa (‘Libya’), by the Ocean |

Note. Relevant excerpts from each source:

|

|

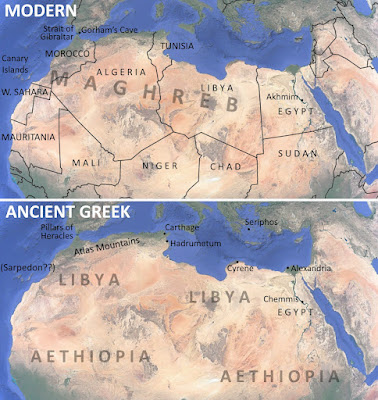

| Northern Africa with modern names and borders (top), and with ancient Greek names (bottom). |

The ancient Greco-Roman imagination gradually shifted the Gorgons’ home, from an island in the Atlantic, eastwards to the African mainland: perhaps in Morocco, perhaps at the Strait of Gibraltar. In 2019 a fragmentary archaic Greek carving of a Gorgon’s head, or Gorgoneion, was found in Gibraltar itself deep inside Gorham’s Cave.

The Cypria’s island of ‘Sarpedon’ may be purely imaginary — though I do wonder if it may reflect a very early awareness of the Canary Islands (just over 100 km from the mainland, and inhabited in antiquity, most likely by Berber people). Stesichorus (500s BCE) also mentions the ‘Sarpedonian island’ in connection with the story of Chrysaor, who sprang from Medusa’s neck after she was beheaded. (Pindar puts the Gorgons in or near Hyperborea, a fictional place in the far north. We can leave that aside: Hyperborea was sometimes imagined as being in northern Ukraine, or to the north of the Caspian Sea.)

| Note. Stesichorus: Geryoneis fr. 6 ed. Davies and Finglass = PMG suppl. fr. 86. |

Herodotus is responsible for much of the misunderstanding over Medusa being ‘Libyan’. He identifies the Greek Perseus with an Egyptian cult in the city of Chemmis, and writes as if all of Libya and Egypt are in the same direction from Greece:

(The Egyptians) actively avoid practising Greek customs ... but there is a great city in the nome of Thebes called Chemmis ... and in this city is a square shrine of Perseus, son of Danae. ... [The Chemmites claim that Perseus] came to Egypt for the same reason that the Greeks say, to bring the Gorgon’s head from Libúē. They said that he came to their city too and acknowledged his relatives there ...

Herodotus 2.91 (tr. Gainsford)

Herodotus always calls Egyptian divinities by Greek names, when he can. When he describes a festival of Osiris at Siwa, for example, he calls the god ‘Dionysus’, because of some minor parallels with Greek Dionysiac festivals (2.47–49). He goes on to express an opinion that most Greek gods’ names originally came from Egypt (2.50).

Translating names in this way is called interpretatio graeca. Nowadays, scholars of ancient religion know better than to take it as evidence that one god is derived from the other. Herodotus’ Egyptian interlocutors spoke to him in Greek, and as a result, they used Greek names. That’s clear from his description of the ethnic mix at Siwa (2.43): he tells us that the people there were a mix of ‘colonists from Egypt and Ethiopia, and they customarily use speech that is in between both.’ He was well aware of ethnic differences between Siwa and the Nile valley, but interpreted them in terms that were familiar to him. Nowadays Siwa is mostly Berber.

Herodotus gives us valuable data, but he’s no authority in interpreting the data. He’s entirely wrong about Greek gods’ names, for example: we know now that they’re mostly Indo-European. The leading candidate for the Egyptian deity at Chemmis that he calls ‘Perseus’ is Horus. There was a myth at nearby Antaeopolis that Horus made a pair of sandals from the hide of Seth; Perseus’ flying sandals would have made an obvious parallel. (See further Lloyd 1994: 367–369.)

A glance at a map, and a review of the other ancient sources on Medusa, makes the situation totally clear. The Perseus legend didn’t originate in Chemmis; Medusa and the Gorgons didn’t originate in the modern territory of Libya. The Gorgons were in the far west.

And, incidentally, Gorgon snake hair in Morocco certainly isn’t derived from Maasai dreadlocks in Kenya. (Yes, I’ve seen this claimed.)

|

| Left: a Gorgoneion or Gorgon’s head on a hydria from Attica, Greece, ca. 490 BCE (British Museum 1867,0508.1048). Right: a reconstruction of the Gibraltar Gorgoneion, found in Gorham’s Cave in 2019 (Gibraltar National Museum; source: Gibraltar Chronicle, 19 May 2021) |

Is Medusa African nowadays?

As I said at the start, it’s entirely a matter of what people want. If Medusa is African at all, she’s going to be Berber. So if Berber people want Medusa to be Berber, then yes, she’s Berber.

But it does seem to me that it isn’t Berber people who want to claim Medusa. When people do claim that she’s an African divinity, or an African symbol, it generally seems to be in the context of framing ethnicity in terms of ‘black’ and ‘white’.

The story of Medusa was created by Greek society to demonize black women, specifically those involved in traditionally African spiritual practices, with the hopes of discouraging race mixing with the genetically dominant melanated masses and maintain white genetic survival.

Jason Williams, ‘The story of Medusa is about European fear of African spirituality, melanin and black women with power’, 2019

This framework slots all European and African people into either ‘black’ or ‘white’ pigeonholes. Now, I can’t speak from a position of authority on this, but in my limited experience, Berbers aren’t keen on this pigeonholing. The pigeonholes aren’t designed with Berber people in mind — even though Berbers are regularly pigeonholed as ‘black’ by both white supremacists and black afrocentrists.

‘White’ and ‘black’, as a taxonomy of race, are inventions of the modern era. Ancient people were racist too, but they tended to think of ethnicity in terms of homeland, language, clothing, religion, and other customs, all in a bundle. An Ionian Greek city could change its ethnicity by changing its dialect and clothing styles. Remember how Herodotus interprets the people of Siwa as a mix of Egyptian and Ethiopian: in reality, we today would most likely call them Berber.

‘Berber’ itself isn’t a grouping by skin colour, it originated as a linguistic grouping. Berbers are people that speak one of the Berber group of languages — Tamazight, Shawiya, Tuareg, and so on. Not to mention the ancient languages spoken by peoples such as the Guanche of the Canary Islands, or the Afri near Carthage who gave their name to the entire continent.

Anthropologists and historians regularly tell us, in fact, that ‘Berber’ as an overarching ethnic category is a comparatively recent phenomenon. It’s partly the doing of Arab invaders in the mediaeval period; partly the doing of 20th century French colonial strategy in Morocco and Algeria, casting ‘Berber’ and ‘Arab’ as non-overlapping categories so as to divide and conquer — ‘to foster strong Berber support for the French presence’ (Moore 1974: 384; see also, in much greater detail, Rouighi 2019a, esp. 133–163; 2019b). Even the name ‘Berber’ is generally thought to be an imposition from the Latin language — either directly, from Latin barbarus, or indirectly, via mediaeval Arabic بربر.

It’s entirely up to Berber people to decide whether Medusa is African today. I can’t read Tamazight or Arabic, so I’m not ideally placed to say what the prevailing mood is. I haven’t found any Berber sources that incorporate her into Berber iconography or culture. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t any. And either way, she can still become Berber any time.

References and further reading

- Lloyd, A. B. 1994. Herodotus book II. Commentary 1–98, 2nd edition. Leiden.

- McDaniel, S. 2020. ‘Where does the myth of Medusa come from?’ Tales of Times Forgotten, Oct. 2020.

- Moore, C. H. 1974. ‘The Berber myth and Arab realities.’ Government and opposition 9.3: 384–394. [JSTOR link]

- Rouighi, R. 2019a. Inventing the Berbers. History and ideology in the Maghrib. Philadelphia.

- Rouighi, R. 2019b. ‘How the West made Arabs and Berbers into races.’ Aeon 18 Sep. 2019.

Thank you for the reference in the "further reading" section!

ReplyDeleteYou probably didn't notice this, but I actually address nearly the exact same claims that you address here about Medusa having supposedly originally been an African goddess with dreadlocks in an answer I wrote over a year ago on Quora—on the exact same day that I posted the article on my blog that you've linked here, as it happens.

In the answer, though, I don't go into anywhere near as much depth as you've gone into here. I mostly just say that, although Herodotos does say that Medusa lived in North Africa, there's nothing to indicate that she was originally an African goddess and the story of Medusa was most likely made up by Greeks.

The main thing that my answer adds to what you've said here is that I actually address the claim about the dreadlocks by pointing out that the earliest surviving depictions of Medusa, including the famous Kykladic pithos from the early seventh century BCE that depicts her with the lower body of a four-legged horse, don't seem to depict her with snakes for hair. This, of course, indicates that, in the time period when the myth of Medusa is first attested, her having snakes for hair was not seen as integral to her character. Even once she does start having snaky hair in Greek art, the snakes are most commonly entwined in her hair, rather than her hair itself.

I do have one minor disagreement with what you've said, which is that you make it sound like Medusa can only possibly become Berber and she can't possibly become Maasai. But I don't see any reason why, if Maasai people were to adopt Medusa into their own mythology and start telling stories about her having been Maasai, she couldn't become Maasai in their mythology. Myths are malleable, after all. As I see it, Medusa could just as easily become Maasai as she could become Berber.

Thanks for the comment and the Quora link. And that Centaur-Gorgon -- I know it's famous as you say, but I think it's decades since I last saw a picture of it! It completely passed me by.

DeleteOn reflection you have a point about Maasai Medusa. It's founded on a distortion, but as you say, myths are malleable. My last sentence — 'But that’s a long, long way from making her Maasai' — was ill-advised. If you don't object I'll delete it from the article and just preserve it here in this comment.

I don't object to you removing the last sentence at all.

Delete