In September 2019 the Gibraltar National Museum announced the find of a fragmentary Gorgoneion, a Greek artistic representation of a Gorgon’s head, at Gorham’s Cave in Gibraltar. It was made out to be a pretty big deal, and the find was formally published in PLoS ONE last month, in April 2021.

And it genuinely is the real deal. This Gorgoneion is a very significant find. But there are some extreme claims out there:

The location of the finds, in the deepest part of the cave, appears to give support to the myth and its location.

Government of Gibraltar, 19 Sep. 2019

Very rarely, archaeology confirms a myth. The discovery, in Gorhams Cave, Gibraltar, of fragments of a Gorgoneion ... is one example.VisitAndalucia.com, 9 Jan. 2021

|

| Left: fragments of a Gorgoneion found in Gorham’s Cave ‘over several archaeological seasons’ (dates unspecified). Right: a reconstruction of the Gorgoneion produced at the Gibraltar National Museum and unveiled on 18 May 2021. (Sources: left, Finlayson et al. 2021: Fig. 3; right, Gibraltar Chronicle 19 May 2021) |

As so often, the problem isn’t the find itself — the Gorgoneion is for real — but the language used.

The Gorgoneion ‘confirms a myth’ ... um, what myth, exactly? That Gorgons are real? That Medusa actually lived at Gibraltar? Obviously not. But that’s what most of the language in the press tries to imply. A much more sensible summary was given by the project lead at the Gibraltar National Museum, Chris Finlayson:

It was a shrine, a place of worship for the ancient mariners. ... We thought it was only holy for the Phoenicians but now we know it was also holy for the Greeks.Chris Finlayson, quoted in The Olive Press, 29 Sep. 2019

No one believes Gorgons are real. So when someone says this Gorgoneion ‘confirms’ a myth, that’s a real problem. The claim is so patently absurd that it poisons the legitimacy of the real story.

That seems like quite a stretch. How can they know that pair of eyes belonged to a gorgon instead of literally any other face?‘Charyou-Tree’, Reddit, 5 Apr. 2021

It is an important find, to be clear, and those eyes are absolutely unmistakeable. But I fear sensationalism has done some damage to this discovery. Chris Finlayson has his feet on the ground, as I mentioned, but even he is subject to the sensationalistic impulse (Finlayson et al. 2021: 1):

The quest for sites and artefacts of classical mythology was the hallmark of archaeology at the end of the nineteenth century. Schliemann’s ... purported discoveries of King Priam’s treasure or the mask of Agamemnon are prime examples of attempts to link material culture to classical stories.

Oh, ye gods and little fishes. It’s bloody Schliemann again.

The authors go on to talk about Schliemann’s ‘controversial results’, and they compare these archaeological sites to the search for Atlantis. Oh help.

Now, ‘controversial’ is a word you could use for Schliemann’s methods (if you were being extremely generous). But the sites aren’t controversial. I’ve pointed this out before many times, but here it is again: Schliemann didn’t ‘prove’ Troy existed, and it never needed proving. The idea that it might have been a myth is itself a myth. The people who lived in Troy from around 700 BCE (the time of Hesiod) to 500 CE (after the fall of the western Roman Empire) would be very surprised to hear that there was such a ‘controversy’ over their bustling city.

Atlantis, by contrast, has nothing real about it whatsoever: Plato devised it around 360 BCE as an ad hoc allegory for Athens’ supposed potential to resist Macedonian conquest, and he based it on stories he had heard about the Atlantic Ocean being unnavigable — stories that were totally false.

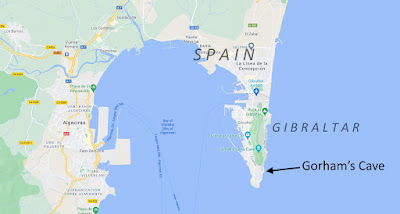

|

| Location of Gorham’s Cave in Gibraltar (source: Google Maps) |

The Gorgons’ link to Gibraltar is similar to the case of Troy. Not because the existence of the place was in doubt: no one ever thought the Pillars of Heracles, as the Greeks called the Strait of Gibraltar, were a myth. The similarity to Troy is because it’s definitely a real place, one that has always been known to be real, and which happens to have a myth attached to it.

New York and Nottingham are real, but that doesn’t mean Spider-Man and Robin Hood are. Real places don’t mean that myths actually happened. Nothing physical about a place ‘confirms’ a myth.

It is legitimate to say that this find confirms that ancient Greeks genuinely drew a link between the place and the myth, and that they did so as early as the Archaic period. Now, for Troy or Mycenae, that would be totally unsurprising. Of course they thought of the Trojan War as taking place at the contemporary city of Troy.

But when it comes to Gibraltar and Gorgons, this statement actually is interesting and significant. Before the Gorham’s Cave Gorgoneion was discovered, there actually was no material evidence that the ancients drew a link between the mythical Gorgons and the real Gibraltar. There wasn’t any particular reason to doubt it, mind: just that, as the April publication puts it (Finlayson et al. 2021: 3),

Until now the interpretation, based on a combination of material culture excavated, and the known presence of these people in the area at the time, has been that they were Phoenician and later Carthaginian mariners. Recent analyses have shown that the material culture found in this level has a broader international character ...

|

| The team at the Gibraltar National Museum at the unveiling of their reconstruction of the Gorham’s Cave Gorgoneion, 18 May 2021 (source: Gibraltar Chronicle, 19 May 2021) |

The Gorgoneion is significant, but not because it proves Gorgons were real. It’s because it’s the first material evidence that Greeks actually did visit Gibraltar. It’s because it’s the only Gorgoneion of its kind in the western Mediterranean. And it’s because it’s in a cave, not a temple. It is genuinely a unique find. There was no permanent Greek settlement at Gibraltar, so whoever put the Gorgoneion there — in a deep part of the cave, no less — made a special visit, and went to some trouble.

... and the Gorgons, who dwell beyond famous Ocean

at the edge of night, the same place as the clear-voiced Hesperides:

Sthenno, and Euryale, and Medusa who suffered evil things.Hesiod, Theogony 274–276

Hesiod’s Theogony dates to around 700 BCE: it is very likely the earliest surviving piece of Greek literature. Already at the beginnings of Greek literature, we see the Greeks locating the Gorgons at the western boundary of the known world. ‘Beyond the Ocean’ suggests something even further afield, but even so, it’s pretty reasonable to interpret the labour taken over the Gibraltar Gorgoneion in light of this passage.

Gorgoneions are a reasonably common sight in ancient Greece itself. But the Gibraltar Gorgoneion genuinely is a big deal. My feeling is that its importance is only undercut by absurd claims of ‘confirming’ a myth.

Reference

- Finlayson, C.; Gutierrez Lopez, J. M.; Reinoso del Rio, M. C.; et al. 2021. ‘Where myth and archaeology meet: discovering the Gorgon Meduas’ lair.’ PLoS ONE 16.4: e0249606.

The publication offers no solid evidence the Gorgoneion was brought and left behind by a Greek, neither that it was deposited shortly after it was produced. It may well have been a votive by a Phoenician or Iberian visitor of the cave, who acquired the piece through trade or piracy. We already know Greeks were in the area decades if not longer before the relief was made, and also that many sanctuaries along Mediterranean trade routes were multi-ethnic and multicultural. I really don't see what the big deal is.

ReplyDelete