The battle of Thermopylae resonates incredibly strongly with alt-right white nationalists. This is especially striking considering that the Spartans lost that battle. And, so far as we can tell, achieved nothing.

|

| ‘White pride’: members of the Shield Wall Network pose with their ‘Spartan’ shields. The lambda symbol adopted by this group in Mountain View, Arkansas, is ‘supposed to signify the defense of Europe against "nonwhite hordes."’ (Source: ADL, retrieved 31/10/19.) |

We’re being topical here, for a change. On Wednesday 23 October 2019, twenty-eight Republican members of the US Congress trespassed in a secure space, or SCIF (Sensitive Compartmentalized Information Facility). Many of them took recording devices, made phone calls, used WhatsApp and Twitter, and took films on mobile phones while inside the SCIF. They delayed the process of law several hours. And not one of them was arrested or charged.

| Note: a press release from the office of Rep. Matt Gaetz named 41 members of Congress; 13 of them were on committees involved in the hearing, and so were authorised to be there (but not to take photos or films). The other 28 were committing a crime. Press release, 22 Oct. 2019. |

The ringleader of the trespassers, Rep. Matt Gaetz, spoke as follows:

Interviewer. Anyway you just single-handedly led a group to shut down this entire impeachment investigation right now. And what were you thinking about?

Gaetz. We were, uhhh ... like ... the 300, standing in the breach to try to stop the radical left from storming over our democracy. And I think we have made the point that President Trump deserves due process.

TMZ, 23 Oct. 2019

Commentators quickly pointed out that Gaetz evidently doesn’t remember the story of the 300 very well. The Spartans who fought at Thermopylae lost. They all died.

What part of the 300’s experience was it most like?

The part where every one of them was killed?

The part where Leonidas’ head was cut off, fixed to a pole and paraded before the cheering Persian troops?

The part where Xerxes took the Spartans’ arms?

Myke Cole, Twitter, 23 Oct. 2019

(Entertainingly, after Gaetz tweeted from inside the SCIF, he realised belatedly that it’s very very illegal to do that. So he posted a follow-up tweet, claiming

**Tweet from staff**

Matt Gaetz, Twitter, 23 Oct. 2019

— presumably hoping no one would notice that his staff tweets are on a different account, and use Media Studio or the Twitter web interface. The problematic tweet was posted on his personal account, using the Android app. Oopsie!)

Thermopylae and the alt-right

Anyway, Gaetz’s language about the 300 is nothing new from alt-righters and white nationalists. Thermopylae, the 2007 film 300, and the 1998 comic book it’s based on, are all part and parcel of the language of modern racism.

To document this fully would take a large book. Tharoor (2016), Bond (2018), and Cole (2019a, 2019b) make a start, though.

Tharoor points out that a motto associated with the 300 Spartans, molōn labe (‘come and get them’), has come to be closely linked to alt-right merchandise, nationalists, and gun rights activists. (See for example here; here at bottom; here.) He mentions a YouTuber called ‘Aryan Wisdom’ who in 2016 edited Trump and his political opponents into scenes from 300.

Bond discusses Steve Bannon’s fondness for Sparta, and the historical use of ‘come and get them’. She gives an incisive analysis of the problematic relationship between Hellenistic-era Spartan propaganda and modern America, especially in relation to eugenics.

Cole reports that in 2012 a representative of Golden Dawn — a Greek political party that instigates racial violence — described present-day immigrants as ‘descendants of the first waves of Xerxes’ army ... wretched people’. A prominent supporter of the terrorist acts in 2011 that left 80 people in Norway dead went by the pen-name ‘Angus Thermopylae’.

In his more recent essay Cole points to an Italian fascist political party using panels from Frank Miller’s 300 in its propaganda posters. He also reminds us that members of the UK Conservative Party’s Brexit wing, the European Research Group, call themselves ‘the Spartans’ — language echoed by the far-right newspaper Daily Mail. I’ll add that according to a March 2019 report, some hard-line Brexiteers refer to themselves as the ‘Grand Wizards’ — in other words, they see ‘the Spartans’ and the KKK as interchangeable.

|

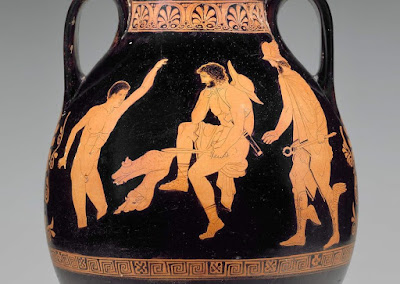

| Leonidas in the film 300 (2007) is modelled on the painting Leonidas at Thermopylae (1798–1814), by the French artist Jacques-Louis David. David carries the main responsibility for the modern myth that Spartans fought in the nude. |

Why does Thermopylae resonate so strongly with racists, nationalists, and terrorists? I can think of a bunch of possible reasons. They’re all based on naive readings of the historical battle.

- Thermopylae can be imagined as a battle for racial purity: ‘pure’ Spartans versus ethnically diverse Persians.

- Thermopylae can be imagined as one force defending its home against an external threat.

- If alt-righters think of themselves as a minority defending a set of values against a tyranny of the majority, they will readily imagine Thermopylae as a tiny force of 300 making a heroic stand against a vast faceless enemy.

- Thermopylae can be imagined as a conflict between individualism and freedom (the Spartans) versus coercion and autocracy (the Persians).

- Thermopylae can be imagined as a religious conflict by proxy: western Greeks stand for Christianity, eastern Persians stand for Islam.

- Thermopylae can be imagined as a case of self-sacrifice, and can additionally be used to rationalise terrorist acts: kamikaze squad and suicide by cop aren’t worlds apart.

- Thermopylae can be imagined as an instance of losing the battle but winning the war.

Each and every one of these characterisations is wrong — or probably wrong — with the partial exception of the last one.

If only that weakened the battle’s potency as a symbol!

The problem is, how the battle is depicted is more important than what actually happened at Thermopylae. These bullet-points, above, that’s how Frank Miller and Zack Snyder depicted the battle. So, in the popular imagination, that’s what Thermopylae represents. In 300 the Persians are darker-skinned than the Greeks, they’re an external threat attacking without any sensible motive, the 300 Spartans are left to fight all alone, Greekness represents freedom, Xerxes represents enslavement, Miller and Snyder are both militant islamophobes. Add in a touch of homophobic/homoerotic self-hatred, and bang, you’ve got 300.

That hasn’t always been the subtext. In the 1962 film The 300 Spartans, the conflict was political, not religious: capitalism versus communism. But the way the battle comes to have this meaning is much the same:

‘O stranger, tell the Spartans that we lie here obedient to their word.’ This last message of the fallen heroes rallied Greece to victory. First at Salamis, as predicted, and then at Plataea. But it was more than a victory for Greece. It was a stirring example to free people throughout the world — of what a few brave men can accomplish once they refuse to submit to tyranny.

The 300 Spartans (1962), closing voice-over

West versus east, Xerxes in blackface, self-sacrifice, losing the battle but winning the war, freedom ... the name of the enemy is different, but the racism and the symbolism haven’t changed much.

The historical battle

I don’t expect to persuade any committed alt-rightists and racists, but for the sake of interest, and for the record, here are a few notes on the real-life battle in 480 BCE.

1. The Spartans lost. Take heed, all self-proclaimed ‘Spartans’. (Incidentally, there have been several battles of Thermopylae over the millennia, the last one in World War II. The pass has never been defended successfully. See Londey 2013 for full details.)

2. The Spartans didn’t stand alone. They were a minority of the southern forces — only about 5% of the force initially stationed there, less than 15% of the force that remained and died. Besides the Spartans there were 700 Thespiaean troops, 400 Thebans, and several hundred Laconian perioikoi and helots; one source reports that there were 700 perioikoi. (Laconia was the region that had Sparta as its capital; perioikoi were residents without citizen rights; ‘helots’ were an enslaved ethnic group.)

3. It wasn’t a racial conflict. There were more Greeks fighting for Xerxes at the battle than against him. Herodotus reports a figure of 300,000 Greeks in Xerxes’ army. That’s certainly an exaggeration — Xerxes’ entire army probably didn’t have that many soldiers — but we can be certain that it was still more than the 11,000 or so southerners defending the pass. There’s an excellent chance that the defenders were slain by Greeks. This was a north-south conflict as much as a west-east conflict.

4. It wasn’t an ideological conflict. Various parties involved did use religion for propaganda purposes — Xerxes, on his way over to Greece, supposedly paused at Troy to make sacrifices to Ilian Athena, and visited other cult-sites too — but it was certainly not grounded in religion.

It wasn’t a conflict of political systems either. Yes, Persia was ruled by a single king, while the Greek world was a cluster of city-states, but Persian subjects typically enjoyed greater freedoms and economic benefits than people in Greece did. (Go ask one of the Spartans’ helots how much Greek ‘freedom’ is worth.)

Persia wasn’t simply making a territory grab. They were dealing with a clear and present danger. Their territorial possessions in Anatolia and the east Aegean had been threatened by Greek unrest for decades, so from the Persian perspective, mainland Greece was a threat that had to be neutralised. (A nationalist might argue that Persia didn’t have a legitimate claim to those territorial possessions: if you want to play that game I’ll be happy to shift the goalposts too.)

5. It (probably) wasn’t a heroic self-sacrifice. Not intentionally, anyway. That’s how ancient sources cast it — but these are the same ancient sources that tell us in tremendous detail what happened towards the end, when there were supposedly no witnesses who survived.

Some historians in the modern era have seen the battle as a heroic self-sacrifice too — Paul Cartledge (2006: 130) compares them to Japanese kamikaze pilots — but it’s never backed up by any reasoning. There’s no good reason to think of self-sacrifice as an effective strategy. There was nothing to be gained from suicide by cop suicide by Persians.

And don’t go suggesting that a three-day delay was an essential military goal, to get Athens evacuated or something like that: even ancient sources don’t try to get away with that notion. The ancient writers suggest instead that the idea was to delay the northern forces until reinforcements could arrive. Even if there’s any truth to that, it still isn’t the whole story. If reinforcements had arrived, there was no way they could engage the northern army. The whole point of Thermopylae was that it was too confined for a large engagement.

One thing that the ancient sources do agree on is that Leonidas ordered a withdrawal of the bulk of the southern forces. The question is whether the Thespiaeans, Thebans, and Spartans remained to spend their own lives in cover the retreat of the other southern forces, or whether it was supposed to be a graduated withdrawal — that the Thespiaeans, Thebans, and Spartans were intending to withdraw too.

My money is on the latter. The remaining troops would cover the general retreat, then they would leave as well. It should have been a full withdrawal, like that of the Greeks who defended Thermopylae against the Celts in 279 BCE, or the ANZACs who defended it against the Fascists in 1941. However, Persian troops managed to scale the hills and get in behind the defensive line. That’s the reason that the southern Greeks were surrounded and cut off. It was too late to complete the withdrawal, and so they died.

|

| Some of the key locations and cities involved in the battle of Thermopylae |

Chris Matthew goes further. He argues (2013: 73–83) that Leonidas’ intent was actually offensive, not defensive. Before Leonidas ordered the withdrawal, there were somewhere between 6000 and 11,200 infantry stationed there, with a naval force of 280 ships and over 50,000 men stationed at Artemisium. The southerners may well have believed that that was plenty to hold the pass — 10,000 infantry had been stationed for the defence at Tempe, further north. Matthew proposes that the idea wasn’t simply to delay Xerxes’ army, but to trap it in a position where it had no access to food or water. The figures we have for Xerxes’ army are outrageous — ancient sources claim he had 1,700,000 Persians and 300,000 Greeks — but even if we assume these numbers are exaggerated by a factor of 20, the northern army was far too large to live off the land while staying in one spot. Eight years after the battle the playwright Aeschylus wrote that

The land itself is an ally to [the Greeks] ...

killing with hunger an army that is far too numerous.

Aeschylus, Persians 792–794

If the southern force could delay Xerxes for even a week, and southern reinforcements came via another pass and appeared behind the northern army at Heraclea in Trachis, Xerxes’ forces would be trapped at the very moment that they were weakening from hunger, thirst, and disease. The southerners might have annihilated them. But, as it turned out, they couldn’t hold the northerners that long. Leonidas only managed three days. It wasn’t enough.

6. The 300 Spartans weren’t Leonidas’ personal guard. This myth is widely reported in modern accounts of the battle, and also in 300. The idea is supposedly that Sparta refused to engage its military officially, because of a religious festival or for some other reason, and so Leonidas decided to ‘go for a walk’ with his own retinue. In reality they were regular soldiers, sent by the Spartan state in an official capacity. The actual royal guard was 100 in number, not 300, and their function was to protect the king(s) while officially on campaign (Herodotus 6.56). Matthew shows that 300 was a typical number for Spartan contingents on special assignments (2013: 71–72).

7. Spartan soldiers weren’t invincible killing machines. The typical alt-right caricature of Spartan soldiers is an anachronism. The Spartan agōgē as seen in 300, the idea that a Spartan phalanx was unbeatable in the field, the trope of ‘Never give up, never surrender’ — all these things were invented as Spartan propaganda, centuries after the battle.

In the 300s BCE, Sparta was reduced to a minor power with big ideas about itself. The south did not rise again. Instead, Sparta drew on its propaganda successes from the 400s BCE to create a national image of a glorious past, which ended up being more for the tourist trade than anything else. Plutarch’s stories of Spartan military training and Spartan laconicisms are products of that period of self-invention.

Late archaic/early classical Sparta did have a better organised military than most other states, that much is true. They were very good at propaganda — why else would a crushing military defeat like Thermopylae be celebrated? But they didn’t have their well organised military because they were autonomous freeholders, as the likes of Victor Davis Hanson fervently believe. They were able to specialise because they owned an ethnic slave caste.

There’s probably some truth to the notion of a Spartan ‘heroic code’, as idealised in the poetry of Tyrtaeus. But then again, Tyrtaeus wasn’t Spartan. He was an immigrant. Tyrtaeus was a weeaboo. If you look at actual Spartan poetry, by Alcman, you’ll see it’s largely about men leering at dancing girls.

|

| Some outstanding spear-throwing from The 300 Spartans, 1962. (Hold up ... why are they throwing their spears?) |

Despite their military specialisation, the Spartans were very beatable. When a Spartan hoplite phalanx faced another hoplite phalanx, sure, they’d never be at a disadvantage. But when they faced mixed forces and mixed tactics, they regularly lost. The first time a band of Spartan hoplites threw down their shields and surrendered unconditionally in a land battle was at the hands of archers and slingers. And Thebes found out in 371 BCE that, even in a phalanx-on-phalanx situation, Spartans could be totally trounced. When Sparta tried to resist Roman forces in 196 BCE, their soldiers fled for their lives at the sight of Roman standards; the Spartan king Nabis made a complete capitulation after three days of fighting (Livy 34.28-40).

Being Spartan wasn’t about independence and choice. It was about exerting power over other people. They weren’t racially pure plucky freeholders: they were just people. They had a powerful city-state, and the power of that city-state rested on slavery.

And often, it seems, three days was all it took to beat them.

References

- Bond, Sarah E. 2018. ‘This is not Sparta.’ Eidolon, 8 May 2018.

- Cartledge, Paul 2006. Thermopylae: the battle that changed the world. Pan.

- Cole, Myke 2019a. ‘How the far right perverts ancient history — and why it matters.’ Daily Beast, 2 Mar. 2019.

- Cole, Myke 2019b. ‘The Sparta fetish is a cultural cancer.’ The New Republic, 1 August 2019.

- Londey, Peter 2013. ‘Other battles of Thermopylae.’ In Matthew and Trundle 2013: 138–149 and 208–211.

- Matthew, Christopher 2013. ‘Was the Greek defence of Thermopylae in 480 BC a suicide mission?’ In Matthew and Trundle 2013: 60–99 and 178–196.

- Matthew, Christopher; Trundle, Matthew (eds.) 2013. Beyond the gates of fire. New perspectives on the battle of Thermopylae. Pen & Sword.

- Tharoor, Ishan 2016. ‘Why the west’s far right — and Trump supporters — are still obsessed with an ancient battle.’ The Washington Post, 7 Nov. 2016.

[Note: edited two days after initial post. In the previous version I missed Sarah Bond’s essay for Eidolon, which I regret.]